Selecting a Style

This article explains how to select the right software architecture style by using measurable quality attributes, considering real-world constraints, and conducting small, reversible experiments. Learn to make evidence-based decisions that align with your system’s needs and your team’s capabilities.

What “selecting a style” really means

Choosing an architecture style is less about fashion and more about fit. This article outlines a practical approach to decision-making, utilizing quality attributes, constraints, and evidence rather than trends.

An architecture style is a high-level structural pattern that shapes how a system is decomposed, deployed, and evolved. Selecting a style means choosing the dominant structural approach—and its constraints—that best satisfies your system’s quality attributes (e.g., availability, modifiability) while remaining feasible for your team and environment. You are committing to trade-offs: every style amplifies some qualities and suppresses others.

Start from outcomes, not structures

Selection begins with outcomes, not with the catalogue of styles. Define the behaviors and qualities your system must demonstrate under real-world conditions, including load peaks, failure modes, deployment cadence, regulatory events, and organizational changes. If these aren’t explicit, you will optimize for whatever seems easiest or trendiest, and you will likely discover gaps in production.

Quality attributes drive the decision

Translate outcomes into measurable quality attribute scenarios. Each scenario should state a stimulus, environment, expected response, and response measure.

- Performance: A burst of 10,000 concurrent users during a campaign should keep p95 latency under 200 ms.

- Availability: A single-node failure must not exceed 60 s of user-visible disruption.

- Modifiability: A schema change in an isolated domain should deploy to production within one day without coordinated releases.

- Operability: A failed dependency should be detected and isolated automatically, with MTTR under 15 min.

These scenarios become the yardstick for judging styles, not just features.

Fit the style to the environment you actually have

Architecture does not operate in a vacuum. Consider the constraints that will make or break your choice.

- Team topology and skills: Can your teams own services end-to-end? Do you have operational and SRE maturity for distributed systems?

- Runtime platform: Cloud, on-prem, hybrid—each changes networking, storage, identity, and deployment constraints.

- Data gravity and governance: Where data lives and how it is controlled will steer decomposition and integration.

- Compliance and risk posture: Auditability, residency, and change control can rule out otherwise attractive options.

- Delivery cadence: Weekly vs. quarterly releases imply very different coupling tolerances.

A style that ignores these realities will fail, even if it “works” in slides.

Design Considerations

Compare candidate styles with evidence

Use a lightweight, repeatable comparison so decisions are transparent and defensible.

Define 2–3 credible candidates: Avoid false choices. If you have one real option, you don’t have a decision—gather another.

Map each candidate to the same scenarios: For every quality attribute scenario, write a short, concrete response of how the style meets it (or not). Be explicit about mechanisms (e.g., backpressure, bulkheads, blue/green).

Identify primary risks and mitigations: Note what could go wrong: cascading failures, data consistency drift, coordination overhead, debugging complexity. Pair each risk with its corresponding mitigation and associated cost.

Prototype the riskiest assumption: Run a focused spike: e.g., can event-driven ingestion keep p95 under target with realistic payloads? Measure, don’t guess.

Record the decision: Capture an ADR that states the decision, alternatives, trade-offs, and expected review date. Make it easy to revisit with new evidence.

What different styles optimize (and sacrifice)

- Layered/Monolithic: Optimizes simplicity, local reasoning, and throughput with minimal operational overhead. Sacrifices independent deployability and fine-grained scaling as size grows.

- Modular Monolith: Balances simplicity with internal boundaries and stricter layering. Sacrifices some runtime independence to maintain a small operational surface.

- Service-Based / SOA (coarse-grained): Optimizes organizational alignment and reuse of business capabilities. Sacrifices local changes that cross service boundaries.

- Microservices (fine-grained, independently deployable): Optimizes team autonomy, selective scaling, and velocity in heterogeneous domains. Sacrifices operational simplicity; increases failure modes and observability demands.

- Event-Driven: Optimizes decoupling, elasticity, and temporal independence. Sacrifices debugging ease and global consistency; requires mature telemetry and contracts.

- Space-/Cache-Centric: Optimizes extreme read scalability and low latency. Sacrifices simple correctness; pushes complexity into cache invalidation and write paths.

Choose deliberately based on what you need to be great at—and what you can afford to be average at.

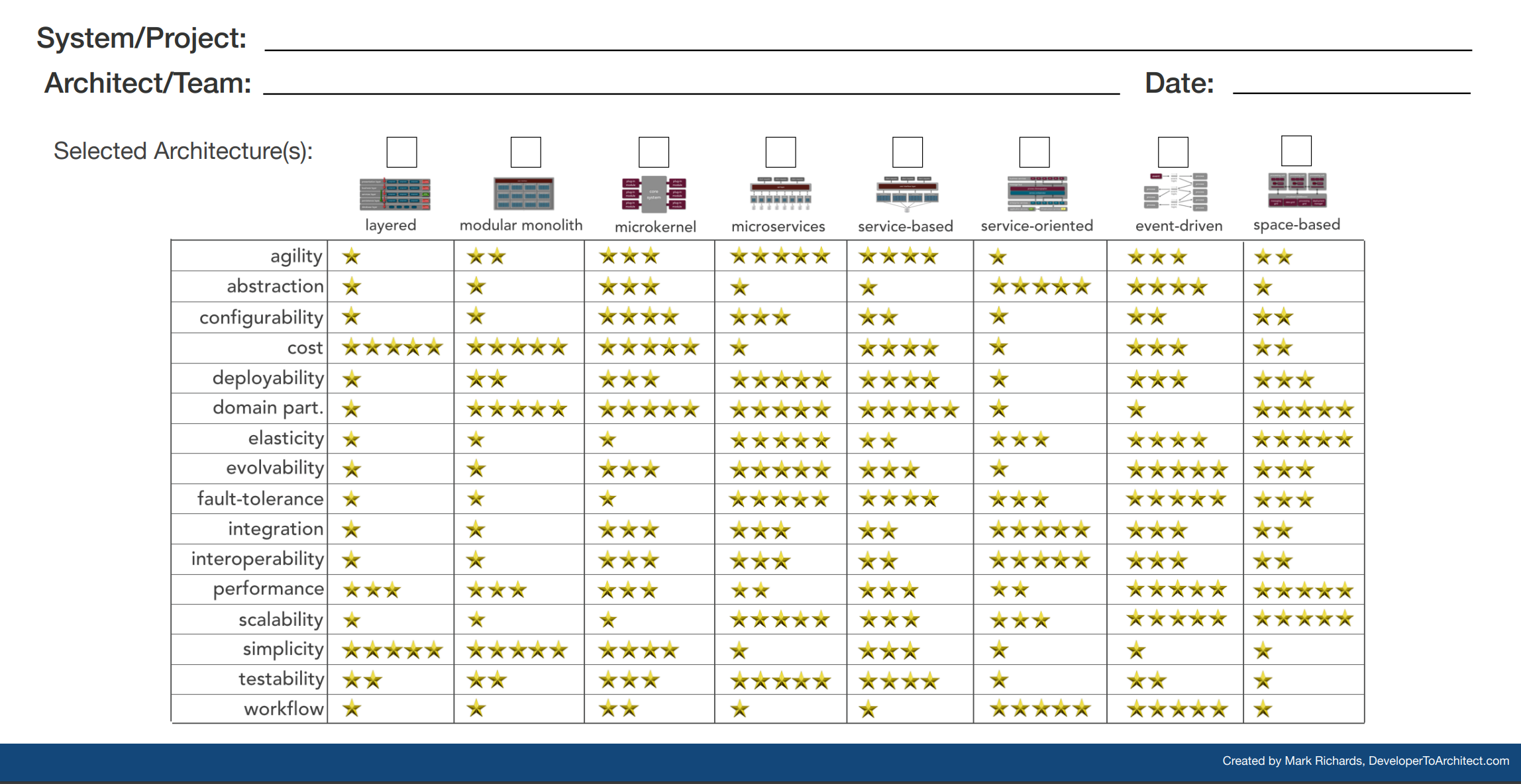

Style–Attribute Scorecard

Illustrative matrix for comparing common styles across selected quality attributes. Created by Mark Richards, DeveloperToArchitect.com. Treat the stars as directional, not absolute; confirm with scenarios and experiments in your context.

\Anti-patterns that derail selection

- Resume-driven design: Picking microservices or streaming because it’s fashionable.

- Premature distribution: Splitting into services before you have observability, deployment automation, or clear boundaries.

- Cargo-cult resilience: Adding queues, retries, and circuit breakers without understanding backpressure and failure amplification.

- Ignoring data: Choosing structure first and forcing data to fit, leading to brittle workflows and ad-hoc integration glue.

- One-way doors: Baking style-specific tech into every corner so change becomes prohibitively expensive.

Make style a small reversible bet

Styles feel irreversible when they’re entangled with every tool and practice. Reduce lock-in by isolating the bet.

- Keep interfaces explicit and versioned (contracts, schema evolution).

- Centralize cross-cutting utilities behind adapters (telemetry, authn/z, messaging).

- Pilot the style in a single slice with real users and production-like data.

- Set a review horizon (e.g., 3 months) tied to measurable outcomes.

Reversibility increases courage to choose—and discipline to back out if needed.

When to evolve the style

Styles should change as reality changes.

- Boundary friction grows: Cross-service changes dominate; consider consolidating (toward a modular monolith or fewer services).

- Velocity stalls under size: Monolith coordination drags; consider extracting hot spots with clear seams.

- Quality targets shift: New attributes (e.g., auditability, multi-region) demand structures that support them first-class.

- Org/topology changes: New teams or ownership lines make a different decomposition natural.

Plan for evolution in your ADR: what signal triggers re-evaluation, and what first steps you’ll take.

Decision checklist

- Do top quality attribute scenarios have measurable thresholds?

- Can your team operate the failure modes the style introduces?

- Do data placement and consistency needs fit the style’s default patterns?

- Is there a small slice to pilot with production-like load?

- Is the decision captured in an ADR with an explicit review date?

Recommended Reading

Web Resources

- Software Architecture Guild, Architecture Process: How to Translate Requirements into a Technical Solution

- Developer To Architect, Choosing The Right Architecture

Books

- Richards, M., & Ford, N. (2020). Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach . O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 18: Choosing the Appropriate Architecture Style

A concise, scenario-driven approach to selecting styles by quality attributes, risk, and organizational context.

- Chapter 18: Choosing the Appropriate Architecture Style