Pipeline Monolith

This article explains the Pipeline Monolith architecture style, detailing its structure of sequential stages and data flows. Learn about its benefits, such as modularity and localized tuning, as well as its trade-offs and practical strategies for scaling and error handling in a pipeline-based system.

Definition

A pipeline monolith organizes one deployable application as a sequence of well-defined stages connected by data flows. Each stage performs one job, passes its results to the next, and can be tuned or parallelized without compromising the system’s integrity. This style fits workloads that are naturally sequential: ingest → validate → transform → publish, while keeping operational overhead low.

A pipeline monolith is a single process composed of multiple stages that are chained together. Each stage accepts an input, applies a specific transformation or decision, and forwards an output to the next stage. The flow is predominantly one-way; branching and merging are allowed but must be explicit. The essence is stage independence with clear contracts and observable data flow, not a grab-bag of helpers glued together.

Intent & Forces

The intent is to make sequential work explicit, modular, and measurable. Typical forces include the need to process streams or batches reliably, to localize performance tuning to hotspots, and to evolve the pipeline by reordering or replacing stages with minimal risk. The style favors throughput, testability of steps, and flexible composition over ultra-low per-request latency and arbitrary cross-cutting calls.

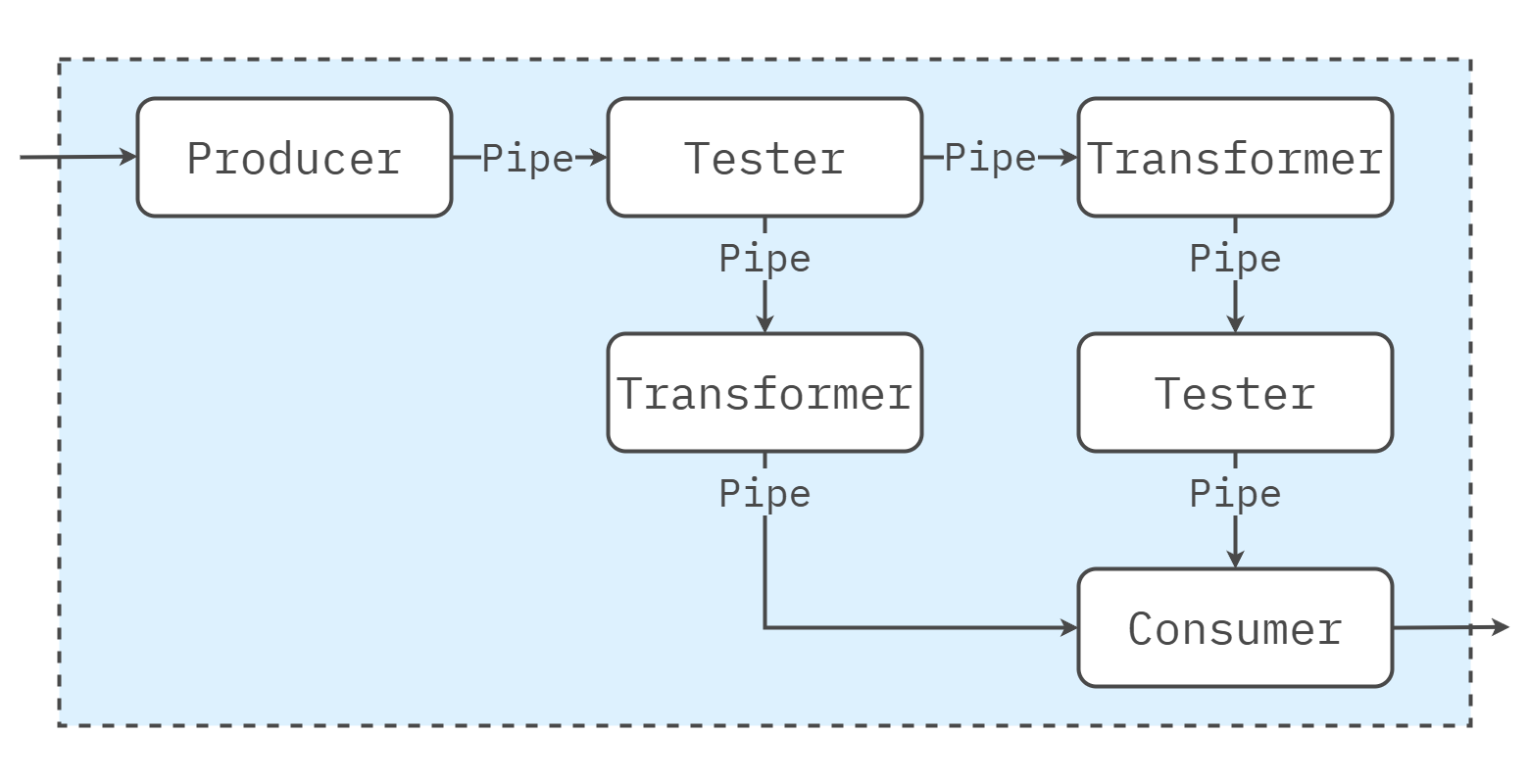

Structure

Think in stages and flows, not layers and services. The structure below can be implemented in most languages and runtimes.

- Elements & responsibilities

- Stages: single-purpose units such as parse, validate, enrich, transform, aggregate, route.

- Connectors: the in-process queues or function calls that move data between stages.

- Deployment units

- One deployable image/process; replicate the whole for HA/scale, or selectively parallelize expensive stages internally.

- Interaction patterns

- In-process hand-offs are synchronous by default; high-throughput paths may use bounded in-memory queues to decouple adjacent stages and absorb bursts.

- Boundaries & contracts

- Typed messages or well-defined record schemas between stages; no hidden out-of-band state.

- Data ownership & flow

- Data is transformed as it moves forward; avoid back-references to earlier stages except through explicit rewind/retry policies.

- Failure domains & scaling

- Failures are contained to the stage currently executing; scale by duplicating that stage’s workers or by sharding the input.

Dependency Rules

Stages depend only on the contracts of their immediate neighbors. A stage must not reach into another stage’s internals or shared global state. Branching is explicit (route on content), and fan-in uses a merger stage that defines conflict and ordering rules. Keep utilities domain-agnostic and avoid “god” helpers that smuggle business rules around stage contracts.

Data & Transactions

Design for idempotency at the stage level and for message semantics that support at-least-once processing with deduplication. Where a multi-stage transactional boundary is necessary, keep it short and instrumented; otherwise, rely on compensations and replayable inputs. Use consistent, versioned schemas at the boundaries and minimize per-hop re-serialization cost. Back-pressure is non-negotiable: bounded queues, rate limits, and admission control prevent upstream overload.

Example

Consider an image-processing pipeline: ingest receives uploads, preprocess resizes/normalizes, classify applies a model, and postprocess formats results. Each stage exposes a handler (for example, handle(Image|Tensor|Result)) and produces a typed output for the next. Under load, duplicate the classify workers and shard by image key. If preprocess lags, back-pressure slows ingest rather than dropping images. Errors at classify move items to a retry lane with a cap and jitter; repeated failures are directed to a dead-letter stage for inspection.

Design Considerations

Where It Fits / Where It Struggles

The pipeline monolith excels in ETL/ELT, event enrichment, content moderation, analytics preparation, and ML inference chains—domains that feature clear, stepwise transformations and measurable throughput. It struggles when the workload is highly interactive with tight end-to-end latency, when steps require heavy two-way coordination, or when consistency guarantees span many stages and long durations. In such cases, shorten pipelines, isolate synchronous “inner loops,” or incorporate request/response patterns for the hot path.

Trade-offs

- Optimizes: modularity of steps, localized tuning, streaming/batch throughput, testability of units

- Sacrifices: lowest possible latency per request, arbitrary cross-stage calls, simple global transactions

- Requires: explicit contracts, idempotency and replay, back-pressure, and end-to-end observability

Misconceptions & Anti-Patterns

- Overloaded stages. A “do-everything” stage defeats modularity and becomes the bottleneck.

- Skipping early validation. Bad records leak downstream and become expensive to correct later.

- Inefficient transformations. Repeated format conversions at every hop burn CPU and time.

- Ignoring back-pressure. Unbounded buffers hide overload until the process reaches its limit.

- Hidden side effects. Stages that alter shared state break replay and complicate error handling.

Key Mechanics Done Well

- Define schemas and contracts first; make stage inputs/outputs explicit and versioned.

- Keep stages stateless or minimally stateful; persist state at well-known checkpoints.

- Instrument queues and stage timers; make bottlenecks visible and cheap to tune.

- Engineer retries with caps, jitter, and dedupe keys; route poison messages to dead-letter handling.

- Use batch windows or vectorized operations in compute-heavy stages for throughput gains.

Combining Styles

Pipelines naturally integrate with event-driven systems (broker at the edges), featuring layered components for administration and APIs, as well as modular-monolith boundaries that reflect the domain ownership of each stage family. Keep the pipeline’s internal flow in-process for simplicity; externalize only where isolation, elasticity, or organizational boundaries make it worthwhile.

Evolution Path

Evolve by inserting, reordering, or replacing stages behind stable contracts. When a single stage dominates cost or risk, consider parallelizing it internally or extracting it as a process with a narrow interface. Treat extraction as an optimization driven by telemetry—stage latency, queue depth, error rates—not by fashion. Keep replayable inputs and deterministic stage logic so you can rebuild outputs when algorithms or rules change.

Operational Considerations

Operate the pipeline as a flow: expose per-stage metrics (arrival rate, service time, queue depth), set SLOs for end-to-end latency and error budgets, and alert on back-pressure thresholds. Standardize logs/traces so you can follow a record through the stages. Rollouts favor canaries per stage behind feature flags. Capacity plans track both CPU-bound stages and I/O-bound hand-offs; tune batch sizes and concurrency accordingly.

Decision Signals to Revisit the Style

Re-evaluate when you see long-tail latency dominated by a single stage, chronic backpressure and dropped work, frequent schema breaks between stages, or rising coordination costs that force cross-stage calls and hidden coupling. If most value now resides in interactive flows, consider shortening or splitting the pipeline to reserve it for asynchronous work.

Recommended Reading

Books

- Richards, M., & Ford, N. (2020). Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach . O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 11: Pipeline Architecture Style

Defines stages and data flows, contrasts synchronous vs. asynchronous hand-offs, and covers bottlenecks, back-pressure, and error handling with practical patterns.

- Chapter 11: Pipeline Architecture Style