Microkernel Monolith

This article explains the Microkernel Monolith architecture style, detailing its core concepts of a minimal kernel and extensible plugins. Learn about its benefits, such as safe customization and extensibility, as well as its trade-offs and practical evolution paths to effectively design and maintain a microkernel-based system.

Definition

A microkernel monolith is one deployable application with a small, stable core and a set of plugins that add or vary behavior through explicit extension points. You keep the core policy tight, push variability to plugins, and gain customization without paying the full distributed-systems tax.

A microkernel monolith separates platform concerns from changeable features. The core hosts contracts, lifecycle, and shared services; plugins implement optional or tenant-specific capabilities that extend these contracts. The essence is a minimal kernel with clear extension points and plugins that can be added, removed, or replaced independently of the core. This is common in IDEs, browsers, and product platforms—and equally valuable for enterprise apps that need controlled customization.

Intent & Forces

The intention is to ensure customization is safe. Teams need to support variations (market, region, tenant, customer) without forking the core or shipping bespoke builds. Forces include frequent change in a subset of policies, the need to ship a stable platform on a predictable cadence, and pressure to enable third-party or internal extensions without risking core stability. The style prioritizes extensibility and modifiability over maximizing raw throughput or adopting the simplest governance model.

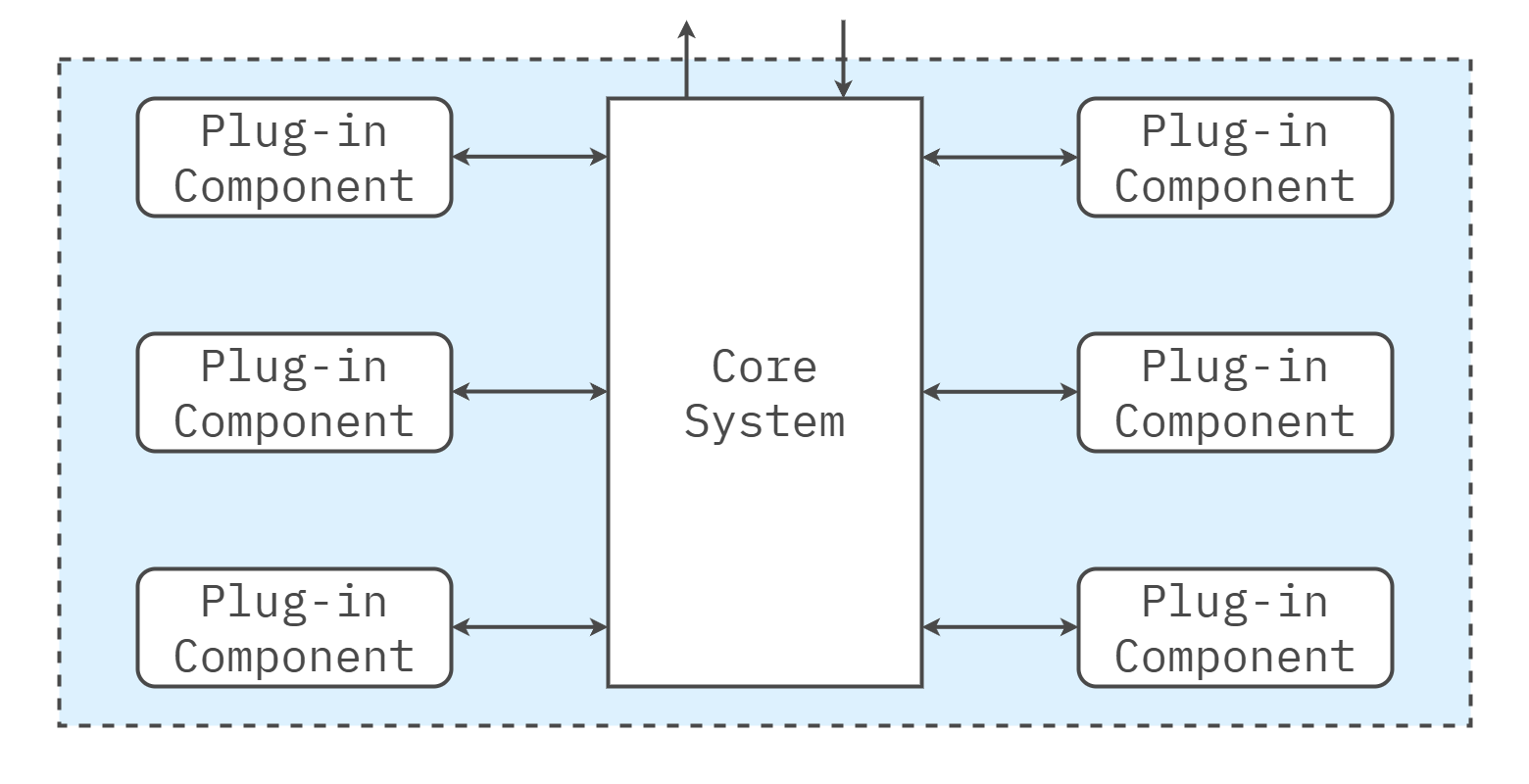

Structure

Think in two parts—core and plugins—with contracts in the seam.

- Core (microkernel): provides hosting, discovery/registration, lifecycle management, and non-negotiable platform policy; exposes extension points and stable APIs/events.

- Plugins (extensions): implement optional or variable behaviors (for example, language support, jurisdiction-specific rules, customer adapters); communicate via the core’s contracts; are loadable/unloadable with isolation safeguards.

Deployment remains a single process/image; plugins reside in separate modules/packages that are loaded by the core. Communication is in process and coarse-grained to avoid chatty paths.

Dependency Rules

Plugins depend on the core’s contracts, not on core internals or each other. Cross-plugin calls are discouraged; if unavoidable, route them via the core so that compatibility and version checks remain centralized. Shared “common domain” libraries are a coupling trap—keep shared utilities domain-agnostic and keep one writer per dataset. Enforce rules with architectural tests (allowed-deps lists, cycle detectors) in CI.

Data & Transactions

Keep authoritative writes within the owning plugin or a core service designated as the broker; avoid direct cross-plugin table writes. If a plugin requires data owned elsewhere, use the owning plugin’s API or core-mediated event streams. Transactions are local to a plugin where possible; cross-plugin workflows prefer events or explicit orchestration through core services. Version schemas at the seam and design for idempotency and replay.

Example

Consider an insurance platform. The core provides intake, authentication, lifecycle, and extension points for Rating and Compliance. A US-Rating plugin implements state-specific rules and registers capabilities; an EU-Compliance plugin enforces GDPR checks. The Claims plugin consumes “PolicyRated” events, but it never accesses the US-Rating internals or its tables. If a regulator changes a rule, only the US-Rating plugin is updated and hot-reloaded; the core and other plugins remain untouched.

Design Considerations

Where It Fits / Where It Struggles

It suits product-style software and internal platforms where customization is a top priority: marketplaces, analytics platforms, content systems, ERP modules, and IDE-like tools. It struggles if the core is volatile (you mis-partitioned) or if plugins must chat heavily with each other on hot paths—both increase coupling and erode the benefits. In those cases, move volatile logic into plugins, coarse-grain interactions, or combine with a modular-monolith structure to align ownership.

Trade-offs

- Optimizes: extensibility, modifiability, product customization, incremental evolution

- Sacrifices: the simplest governance model (you must manage plugin lifecycle and compatibility), some throughput if core↔plugin paths get chatty

- Requires: stable contracts, extension governance (discovery, activation, versioning), sandboxing/isolation, observability per plugin

Misconceptions & Anti-Patterns

- “Microkernel means microservices.” No—start monolithic; distribute only when characteristics demand it.

- Bloated core. If the kernel changes often, volatile logic sits in the wrong place.

- Cross-plugin backdoors. Direct calls or shared tables create hidden coupling; route via the core or events.

- Common “domain utils” that smuggle rules. Keep shared code policy-free; logic belongs in plugins.

Key Mechanics Done Well

- Keep the core small and policy-driven; expose explicit extension points with versioned contracts.

- Make plugins replaceable and additive; publish compatibility metadata and error semantics.

- Add fitness functions: forbid cross-plugin imports, pin allowed dependencies, and fail the build on violations.

- Measure p95/p99 on core↔plugin calls; cache capability lookups; design retries and kill-switches per plugin.

Combining Styles

Microkernel plays well with a modular monolith: treat each plugin as a module with its own layering and data ownership. Event-driven edges are suitable for decoupling plugins that react to core or peer events without requiring direct calls. For admin APIs and UI, a simple layered slice in the core maintains operational surfaces’ coherence. Only externalize plugins (as services) when isolation, autonomy, or technical polyglotism outweigh the added latency and operational costs.

Evolution Path

Start with a minimal kernel and one or two plugins. As variation accumulates, split plugins by capability or jurisdiction, and formalize contracts. If a single plugin becomes a hotspot (due to changes in frequency, risk, or resource usage), extract that plugin as its own process behind the same interface. Treat distribution as an optimization enabled by good extension seams—not as the goal.

Operational Considerations

Plan for plugin governance from day one. Discovery and activation should validate signatures and permissions, check compatibility, and offer kill-switches and quarantine options. Standardize logs, metrics, and traces with plugin identifiers and versions, allowing you to observe behavior per plugin and at the core. For security, put authorization at the core, sandbox plugin I/O and secrets, and audit who loaded what and when. Rollouts favor canary enabling of specific plugins behind feature flags.

Decision Signals to Revisit the Style

Re-evaluate when you notice core churn due to business variation (move logic to plugins), frequent cross-plugin calls on hot paths (coarse-grain or event-based), compatibility/upgrade gridlock, or a security posture strained by untrusted extensions. If most value no longer comes from customization, a more straightforward style may suffice.

Recommended Reading

Web Resources

- Developer To Architect, Lesson 160 - Microkernel Architecture

Books

- Richards, M., & Ford, N. (2020). Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach . O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 12: Microkernel Architecture Style

Defines core vs. plugins, contracts, and extension points, and compares monolithic vs. distributed plugin deployment models with guidance on performance and governance.

- Chapter 12: Microkernel Architecture Style

- Richards, M. (2024). Software Architecture Patterns (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 4: Microkernel Architecture

Explains topology (kernel + plugins), standard product and enterprise use cases, and pitfalls such as bloated cores and cross-plugin coupling.

- Chapter 4: Microkernel Architecture

- Bain, D., O’Dea, M., & Ford, N. (2024). Head First Software Architecture. O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 8: Microkernel Architecture — Crafting Customizations

Shows how to design extension points, govern discovery/activation/versioning, and craft replaceable plugins with precise error semantics and upgrade paths.

- Chapter 8: Microkernel Architecture — Crafting Customizations