Layered Monolith

This article explains the Layered Monolith architecture style, detailing its structure, dependency rules, and data management. Learn about its benefits, such as simplicity and testability, as well as its trade-offs and practical evolution paths to effectively design and maintain a layered monolithic system.

Definition

A layered monolith is a single deployable application organized into a small set of horizontal layers with clear responsibilities. It favors local reasoning and simple operations over independent deploys and fine-grained scaling. If your team needs clarity, safe refactors, and predictable releases, this style is a dependable starting point.

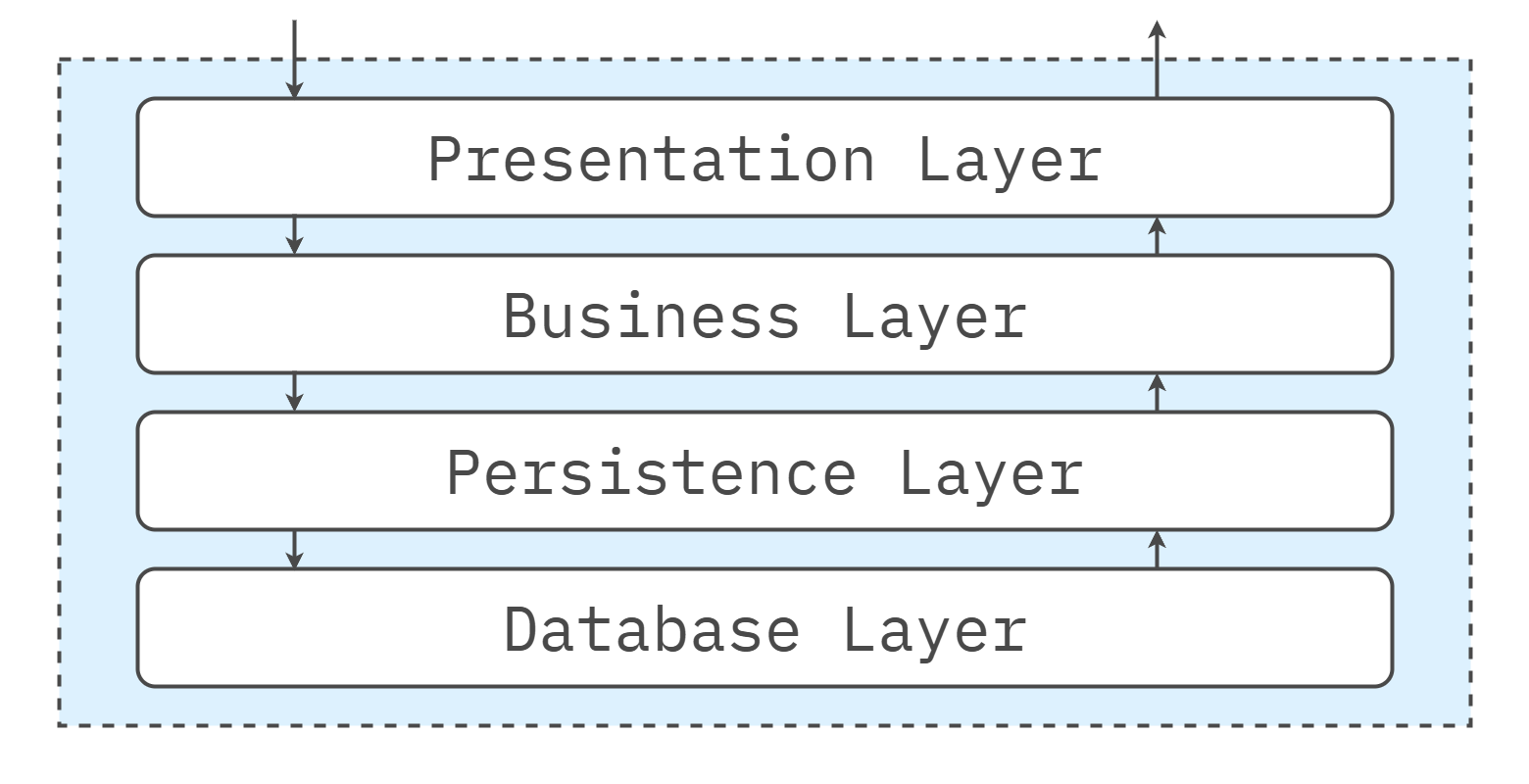

In a layered monolith, code is grouped into layers (Presentation, Application, Domain, and Persistence) and released as one process or image. The dependency direction runs downward only: each higher layer depends on the next lower one, and lower layers remain unaware of higher layers. Layers are closed by default, which prevents shortcuts that couple distant parts of the system. Exceptions exist, but they are rare, explicit, and justified with data.

Intent & Forces

The intent is to reduce cognitive load and keep change local. This style balances common early-stage forces: limited operational maturity, the need for straightforward testing, and a desire for coherent transactions. It prioritizes simplicity and stable seams over distributed autonomy and selective scaling, resulting in a structure that most engineers can quickly understand and evolve safely.

Structure

Think of the layered monolith as a compact stack:

- Presentation shapes input and output, performs validation, and composes UI or API responses.

- Application coordinates use cases, sets transaction scope, and enforces workflow-level policy.

- Domain holds the rules and invariants that give the system its business meaning.

- Persistence reads and writes data and can emit events through adapters.

The application is packaged and deployed as a single artifact. You scale by running more replicas of that artifact. Interactions between layers are in-process calls, keeping latency predictable and observability straightforward. Public interfaces between layers serve as contracts, with contract tests protecting these seams as the codebase grows. Failures occur within the process boundary, so the blast radius is the application itself; guards and graceful degradation in Presentation and Application help contain incidents.

Dependency Rules

The rule set is simple: Presentation → Application → Domain → Persistence. Lower layers never call up. If inversion is required—for example, Domain needs to notify Application—use events or interfaces owned by the caller. Keep layers closed to avoid shortcut couplings. When a narrow exception makes sense (for instance, a read-only projection that bypasses Application to reduce latency), record it with an ADR, cover it with tests, and observe it in production. Exceptions should stay exceptional.

Data & Transactions

Place transaction boundaries in the Application layer and aim for “one use case = one transaction.” Within a request, consistency is strong and predictable. For cross-system propagation, use an outbox pattern and events so the monolith’s internal model remains authoritative. Read-heavy paths can utilize caches or read models, but they should be fed by events or change streams to maintain data coherence over time. Treat schema evolution as a first-class concern: favor additive changes and keep migrations backward-compatible for one release to enable safe rollbacks.

Example

Consider “Place Order.” The request enters Presentation, where it is validated and shaped into a command. The application opens a transaction and orchestrates the steps. The domain calculates prices, enforces policies, and determines state transitions. Persistence commits the changes and emits an OrderPlaced event via an adapter. Control returns to Application to commit or roll back, and Presentation shapes the response. Notice what doesn’t happen: the UI never queries the database directly, and the Domain never formats HTTP or JSON.

Design Considerations

Where It Fits / Where It Struggles

The layered monolith fits product teams that ship regularly, handle mostly local change, and want low operational overhead. It is beneficial when onboarding new engineers or untangling a previously ad-hoc structure. The style struggles when only a small subset of features requires massive scale, when cross-component changes are the norm, or when latency budgets are so tight that pass-through code becomes a measurable drag. In those contexts, you either strengthen seams to prepare for extraction or adopt styles that optimize for isolation and selective scaling.

Trade-offs

- Optimizes: simplicity, testability, onboarding speed, coherent transactions, single-artifact operations

- Sacrifices: fine-grained scaling, fault isolation, polyglot autonomy

- Requires: disciplined boundaries, contract tests, clean dependency direction, baseline CI/CD, and observability

Misconceptions & Anti-Patterns

- “Layers = separate deployables.” Turning technical layers into networked tiers creates accidental distribution and brittle latency chains.

- Skip-the-layer. UI-to-database shortcuts become permanent coupling.

- Leaky rules. Business logic in controllers or DAOs undermines the Domain’s role.

- Pass-through layers. Hops that only shuttle DTOs add latency without value and should be removed or collapsed.

Key Mechanics Done Well

Healthy layered monoliths are component-centric: each business component contains its own slice of Presentation, Application, Domain, and Persistence. That keeps changing locally, making future extraction cheaper. Contracts between layers are explicit and protected with tests. Dependency hygiene is enforced through static checks and CI rules, so back edges and cycles fail quickly. These mechanics keep the style crisp as teams and codebases grow.

Combining Styles

This is not a stylistic prison. You can add event-driven edges to integrate with other systems asynchronously or introduce cache- or space-centric reads for hot query paths, while keeping authoritative writes in Persistence. External services (e.g., payments, identity, search) should sit behind adapters so that their details do not leak into the Domain or Presentation layers. Mixing patterns is safe when boundaries remain intact.

Evolution Path

Evolution typically starts inside the monolith. Strengthen code and data seams around components and align ownership to those seams. When a single component becomes a hotspot—due to load, risk, or velocity constraints—extract that component behind a stable contract rather than splitting by technical layer. If production data or governance requirements necessitate distribution, use strangler techniques to route a slice of traffic and measure the outcomes before expanding the cut. Let evidence, not fashion, drive the pace of change.

Operational Considerations

Operate the layered monolith like any critical service: use a single release pipeline, feature flags for safe rollout, and tracing across layer boundaries. Domain events provide breadcrumbs for operations and analytics. Keep external calls wrapped with timeouts, retries, and circuit breakers where appropriate, and design degradation paths in Presentation and Application so that partial failures do not escalate into total outages. Because you ship a single artifact, rollbacks are simpler—but only if schema changes remain compatible for at least one release window.

Decision Signals to Revisit the Style

Plan a review when you observe sustained trends, such as rising change lead time from cross-component coordination, worsening MTTR (Mean Time to Recovery) because failures take down unrelated features, resource concentration in a small set of endpoints, or muddled ownership where multiple teams change the same internals. These indicators suggest consolidating responsibilities, strengthening seams, or extracting a hotspot.

Recommended Reading

Web Resources

- Developer To Architect, Lesson 158 - Layered Architecture

Books

- Richards, M., & Ford, N. (2020). Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach . O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 10: Layered Architecture Style

Establishes the canonical four-layer structure, explains closed versus open layers with examples, and relates the style to modular monoliths and service-based decompositions.

- Chapter 10: Layered Architecture Style

- Richards, M. (2024). Software Architecture Patterns (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 3: Layered Architecture

Breaks down responsibilities per layer, analyzes the cost of layer-skipping and pass-through code, and contrasts in-process layering with N-tier distribution.

- Chapter 3: Layered Architecture

- Bain, D., O’Dea, M., & Ford, N. (2024). Head First Software Architecture. O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 6: Layered Architecture — Separating Concerns

Presents a step-by-step “Naan & Pop” scenario showing request flow, transaction boundaries, and practical checks that prevent responsibility leaks across layers.

- Chapter 6: Layered Architecture — Separating Concerns