Event-Driven

This article explains the Event-Driven architecture style, covering its core components like events, producers, and consumers. Learn about its benefits, such as loose coupling and scalability, as well as its trade-offs, including eventual consistency and debugging challenges, to effectively design and implement event-driven systems.

Definition

Event-driven architecture organizes systems around facts that happen—events—and components that react to them. Producers announce what changed; consumers decide if, when, and how to respond. The result is loose coupling, elastic scaling, and parallel work—at the cost of eventual consistency and more challenging debugging.

In the event-driven style, components communicate by publishing and consuming events such as OrderPlaced, PaymentAuthorized, or DeviceOffline. An event is a record of something that already happened, not a request to do something. Producers publish to an event channel (often a topic); any number of consumers may subscribe. The topology favors fire-and-forget: the producer doesn’t know who is listening or whether anyone is.

Intent & Forces

The intent is to decouple capabilities so they can evolve and scale independently. This style balances pressures such as bursty traffic, non-deterministic workflows, and the need to add new reactions without modifying the source. It privileges throughput, resilience to partial failure, and extensibility over strict sequencing, immediate user feedback, and global transactions.

Structure

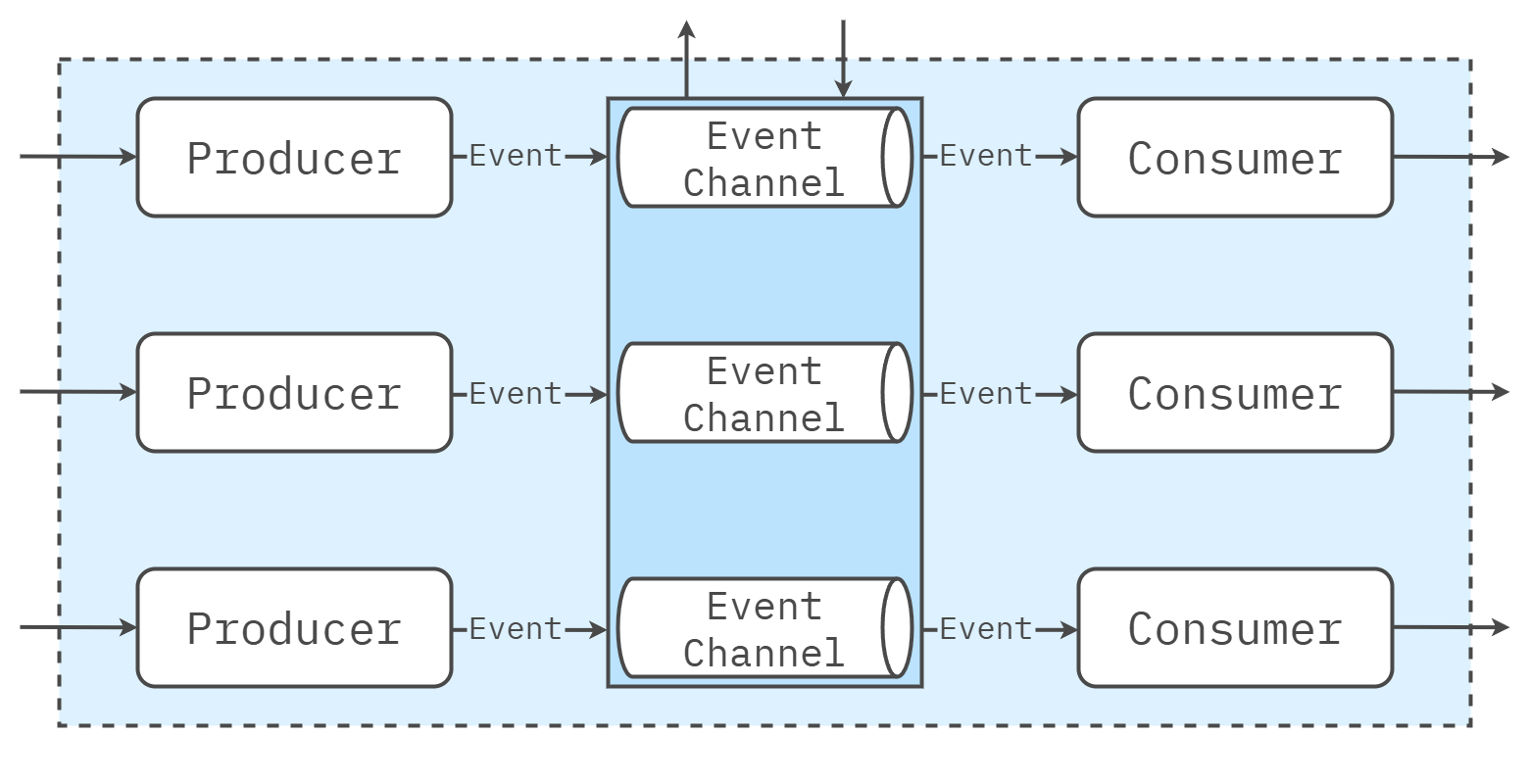

Think in terms of event flows rather than call graphs. The core elements are straightforward:

- Events are immutable facts describing state changes. Good events are named in business language and convey enough context for consumers to act without requiring multiple rounds of communication.

- Producers publish events after they commit their own changes; they don’t wait for consumers.

- Consumers subscribe and react—updating read models, kicking off workflows, or emitting derived events.

- Channels carry events. Point-to-point queues are suitable for triggers that require exactly one consumer to handle; pub-sub topics are better suited for state changes that may be of interest to many consumers.

- Processing models range from simple handlers to complex event processing (CEP) that detects patterns across streams.

This structure invites fan-out: a single initiating event often spawns several derived events as independent consumers do their work.

Dependency Rules

Coupling should run through event contracts—not through shared databases or backdoor calls. Producers must not depend on consumers. When a consumer needs data that it doesn’t own, it prefers an event-carried state or a local read model over synchronous lookups on the hot path. Avoid chatty cross-component calls that recreate tight coupling; if you must call, make it coarse-grained and resilient.

Data & Transactions

Treat each producer’s write as authoritative and emit events via an outbox so the event stream reflects committed facts. End-to-end transactions across multiple consumers are rare; design for local ACID and cross-component compensations. Consumers must be idempotent and tolerant of at least once delivery. Use versioned schemas (with additive evolution) and correlation IDs to enable the joining of events in logs and traces. Back-pressure belongs in the platform: bounded topics/queues, consumer lag metrics, and admission control.

Example

A user checks out. The Order component validates and commits the order, then publishes OrderPlaced with the order ID, items, and amounts. Inventory consumes OrderPlaced to reserve stock and emits StockReserved or OutOfStock. Billing consumes the OrderPlaced event to authorize payment and emits either PaymentAuthorized or PaymentFailed. Notification listens to both to decide what to tell the customer. None of these consumers calls Order synchronously; each can scale, retry, or roll back independently. Adding a new fraud-detection consumer requires no changes to the producer.

Design Considerations

Where It Fits / Where It Struggles

Event-driven shines when work can proceed in parallel, when the load is irregular, and when extensibility is crucial—such as in analytics pipelines, IoT telemetry, post-order ecommerce work, content moderation, and ML inference chains. It struggles when the UX requires immediate, authoritative answers, when many steps demand strict ordering and timing, or when the domain cannot tolerate eventual consistency. In those cases, keep the interactive inner loop synchronous and push background work to events.

Trade-offs

- Optimizes: decoupling, parallelism, elasticity, extensibility, fault containment

- Sacrifices: simple debugging, global transactions, strict sequencing, immediate feedback

- Requires: idempotent consumers, schema/version governance, observability and correlation, back-pressure, and retry policies

Misconceptions & Anti-Patterns

- “Events are just messages.” Messages direct a receiver (“do X”); events announce a fact (“X happened”). Be explicit about which one you use.

- Shared database coupling. Let events carry state; do not read each other’s tables as a shortcut.

- Over-generic events. Events that mean everything mean nothing. Prefer clear, domain-named facts with stable, versioned schemas.

- Chatty chains. Cascades of tiny synchronous calls between consumers recreate tight coupling and latency problems.

- No dead-letter path. Poison events will appear; handle them deliberately.

Key Mechanics Done Well

- Publish after commit with an outbox to avoid lost/phantom events.

- Make handlers idempotent (keys, dedupe windows) and resilient (timeouts, retries with jitter, DLQs).

- Track flows with trace/correlation IDs end-to-end; instrument consumer lag and topic backlog.

- Evolve schemas additively; keep at least one prior version live; use consumer-driven contract tests.

- Separate initiating events (triggers) from derived events (state changes) to clarify modeling and SLOs.

Combining Styles

Event-driven pairs well with layered slices for admin APIs, with modular monolith boundaries (each module publishes its facts), and with service-based or microservices deployments. Keep the user-facing path synchronous where necessary (e.g., payment authentication), then switch to events for all subsequent processes. CQRS and read models reduce cross-service lookups on hot paths.

Evolution Path

Start with a few high-value events and publish them consistently. Add consumers for read models and downstream workflows. As a component becomes a hotspot, split its responsibilities or deploy it independently—but keep the same event contracts. When schemas evolve, keep old versions available for a sufficient period to accommodate lagging consumers, and retire them in a controlled manner, using telemetry and deadlines to ensure a smooth transition. If flows become too complex to reason about, introduce orchestration for the critical span and leave the rest event-driven.

Operational Considerations

Operate the event fabric like a product: define SLOs for publish-to-consume latency and consumer error budgets; alert on lag/backlog. Standardize logs and traces around event IDs and keys. Plan capacity for partitions, retention, and compaction; rehearse disaster recovery with replay. Roll out changes with canary consumers and shadow topics. Govern access and PII handling at the topic level; audit who publishes and who reads.

Decision Signals to Revisit the Style

Re-evaluate when users need answers now, but you rely on asynchronous chains, when compensation dominates the design, when consumer lag routinely violates SLAs, or when modeling pressure pushes you toward commands and orchestrated workflows. If most flows are synchronous requests, an orchestrated or service-based style may be more suitable; if flows are truly event-centric but debugging is challenging, consider investing in observability and contract governance before adding more consumers.

Recommended Reading

Web Resources

- Developer To Architect, Lesson 165 - Event-Driven Architecture

- Developer To Architect, Event-Driven Architecture Lessons

- Enterprise Integration Patterns, Messaging Patterns Library

Books

- Richards, M., & Ford, N. (2020). Fundamentals of Software Architecture: An Engineering Approach . O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 14: Event-Driven Architecture Style

Defines events, producers/consumers, and channels; contrasts queues vs. topics; and outlines delivery guarantees, back-pressure, and error-handling patterns.

- Chapter 14: Event-Driven Architecture Style

- Richards, M. (2024). Software Architecture Patterns (2nd ed.). O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 5: Event-Driven Architecture

Explains notification vs. event-carried state transfer, shows typical topologies, and highlights pitfalls like over-generic events and hidden coupling.

- Chapter 5: Event-Driven Architecture

- Bain, D., O’Dea, M., & Ford, N. (2024). Head First Software Architecture. O’Reilly Media.

- Chapter 11: Event-Driven Architecture — Asynchronous Adventures

Uses concrete scenarios to contrast sync vs. async, model-initiating vs. derived events, and practice idempotency, retries, and compensation design.

- Chapter 11: Event-Driven Architecture — Asynchronous Adventures

- Bellemare, A. (2020). Building Event-Driven Microservices. O’Reilly Media.

- Practical guidance on event modeling, topic design, consumer scaling, and replay.

- Stopford, B. (2018). Designing Event-Driven Systems. Confluent.

- Event streaming fundamentals, log-centric thinking, and schema evolution with real-world Kafka patterns.

- Hohpe, G., & Woolf, B. (2003). Enterprise Integration Patterns. Addison-Wesley.

- The classic catalog of messaging patterns (pub-sub, message channels, routing, correlation) that underpin robust event-driven designs.